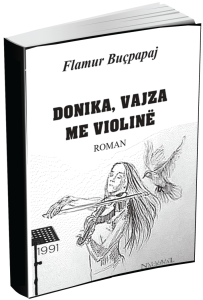

The Wounds of Transition in the Novel Donika, the Girl with the Violin by Flamur Buçpapaj

By Gazeta Telegraf, April 25, 2025

Halil RAMA – Grand Master

As an innovation in this novel, we can highlight the author’s use of a diverse system of structures and artistic conventions, enabling a communicative and dialogic process among deeply engaging characters.

Over the past ten years, the golden archive of Albanian literature has been enriched by the literary work of the now well-known author Flamur Buçpapaj. After four children’s plays, a folklore study, and two novels warmly received by readers — The Second Marriage and The Doctor — this author once again surprises us with his newest novel, Donika, the Girl with the Violin.

And while The Second Marriage has been praised by literary critics as a novel about family renewal, and The Doctor as a literary radiography of the dictatorial system, Buçpapaj’s newest and high-quality novel Donika, the Girl with the Violin exposes the deep wounds of Albania’s prolonged transition, especially those related to prostitution.

THE TIME WHEN “MADNESS OR INTERNAL STRIFE KNOWS NO BOUNDS”

The very title Donika, the Girl with the Violin invites the reader with the expectation that this is a literary biography of a virtuoso artist. But that’s not the whole story. From the very first pages, the author narrates with deep emotion and literary metaphors the drama of this girl caught in the clutches of heartless traffickers. This is clearly seen in the unique compositional form — Donika’s diary — which serves as the prelude to the unfolding of tragic events.

“…handcuffed by both hands and feet, yet this did not prevent her from finding a way to write her diary; to recount what had happened during her abduction… she focused on the pen and the new notebook she had found in that abandoned room — a notebook with three hundred blank pages, which would soon be filled with her neat handwriting. Times were harder now than during the days of poverty. Pluralism brought heavy wounds upon the Albanian people,” she thought. “Many girls and women like me are on the sidewalks of Italy… The long-awaited democracy brought only disappointment, unemployment, and extreme poverty…”

This paraphrase by Buçpapaj is enough to conclude how powerfully he approaches the tragic reality caused by the trafficking of the artist Donika Malaaa, whose violin performances once earned long ovations from her audience. But what happened to her belongs to a time when “Madness or internal strife knows no bounds”… when, as Donika writes in one page of her diary, “Everyone was against everyone,” when concepts like patriotism, citizenship, and brotherhood faded. Her testimony is truly disturbing:

“Instead of loving each other as people from the same city, we feed on one another’s blood. My own fellow townsman, a brother-wolf, did all these terrible things to me: kidnapped me, sold me like a slave… He is Albanian, not a foreigner. Even those who robbed and beat me are Albanians like me, even calling themselves patriots.”

A BRILLIANT PORTRAIT OF THE MAIN CHARACTER

An interesting find by the author is the title of the first diary page, which Donika had hidden in the wall cavity of the old house. It reads in capital letters: “Mrs. Donika, the Girl with the Violin. Stories and events that should never happen.” This is meaningful because later the author presents her as one of the girls who led the December Student Demonstrations.

She is “The girl from Tirana, the first to join the protests that night; the girl who played the violin in front of the lines of communist police, who came to crush or kill us, as we didn’t know what orders they had; the girl who led the students every day through the squares with her violin and her long, blonde braids, with a body like that of a professional sprinter or sculpted in an artist’s studio — more beautiful than the Butrint Dea, blue-eyed, 180 cm tall, with seductive curves like those in foreign fashion magazines, a pure-blooded half-highlander, mixed — Shkodran from her mother and Vlonjat from her father…”

THE “GOOD TIMES”…?!

Based on the above paraphrases, it might seem as though the author reveals the tragic fate of the main character from the very beginning. But that’s not the case.

In the episode The Good Times, the artistic unfolding of Donika’s love story with Ardjan Vusho, a journalist from the North for the newspaper Life Today, is developed.

The highlight here is the dialogue between two student friends, Donika and Moza, on a train ride from Shkodra, and their first encounter with Ardjan. The events are narrated in logical progression up to the moment when Donika, “the superstar of the train from Shkodra” and of the “Institute of Arts,” with sky-blue eyes, tall, bust size 4, with a typically Illyrian-Albanian form (as described by her Art History professor), falls in love at first sight with Ardjan — the blue-eyed heartthrob from Kosovo.

Here, we notice the author’s masterful use of stylistic devices such as personification, rare vocabulary, metaphorical epithets, metaphors, hyperbole, and the rich interplay between characters. This is illustrated, for example, in this paraphrase reflecting the past socio-communist era:

“We are three million and still suck up to capitalism and revisionism. Every time I watch Rai TV, I can’t help but laugh at our old politicians and their guiding light.”

Or in the dialogue:

“And what do you eat at home?”

“Leek stew. Not even potatoes anymore. Look at the empty shops. Bread is rationed too. Cornbread in the village and rationed in the city. These bastards have ‘secured’ bread in the country!” Donika added ironically.

“Hahahaha, how pathetic — we’re a communist people who eat grass and serve Spaç prison, but never violate our principles.” “Be quiet,” said Moza, “or they’ll hear us and we already have our spots reserved in Spaç or Burrel prison.”

“You think there will be vacancies for us?”

“Well, thank God there are!” – They both laughed.

Later, the author stands out as a master in portraying the character of Ardian (Donika’s future husband, who would save her from the clutches of the traffickers), describing him as:

“He didn’t have an ordinary body. He looked enormous, and they had never seen anyone of such dimensions. Jet black hair and eyebrows, slightly dark-skinned with blue eyes, nearly two meters and twenty centimeters tall. He surpassed any actor or boxer, so to speak. They thought he might be a discus or hammer thrower from the Ministry of Interior’s sports teams. This became even more evident when they saw him up close—he met all the criteria of an Olympic athlete, especially when they noticed his size 45 feet and the pair of white sneakers he wore, clearly foreign-made and of a well-known brand.”

THE MASTERFUL USE OF STYLISTIC DEVICES

Even in the novel’s conclusion, the author masterfully uses stylistic devices, giving it a happy ending, which makes it both convincing and at the same time surprising, as Donika thanks God and her husband Ardian. This is clearly reflected even in the following paraphrase:

“Without the Albanian state and the Italian one, I wouldn’t be here. I would have died, because I would never have accepted humiliation or prostitution. I had kept my hopes in God and in my husband, believing they wouldn’t leave me alone. A miracle happened. People, give as much love as you can! I call on everyone, because it was love that united us and saved us from captivity. The letter Ardian sent me in the hospital is a hymn to marital love. I love you Ardian!” she told him.

“I also love Albania, which is still suffering from deep post-communist wounds. Help my homeland, dear Western gentlemen! We are grateful to the Italian state that granted us citizenship and saved our lives. I love you!” she said.

“And I tell you, just like me, there were many girls and women held in captivity from all over the world, who were abused and isolated in sexual slavery. Fight that great evil that is happening! Please, people, believe in God and in your state! The future belongs to the righteous!”